Fright or Delight? Dopamine-Mediated Fear Response in the Amygdala

Blog post by Jasmin Skinner

Dopamine, a neurotransmitter most popularly thought of as the “pleasure hormone,” has far greater roles in fear conditioning than previously thought [1]. Fear conditioning is an evolutionarily-shaped mechanism responsible for aversive memory formation. This response to negative stimuli has been crucial for species survival, as it allows one to predict a negative event based on the association of a previously neutral cue with an aversive stimulus. These neurochemical linkings occur in the amygdala, a brain region that supports associative and emotional learning, and is also heavily innervated by dopamine.

Previous studies have observed a correlation between dopamine signaling in the amygdala and aversive learning, as dopamine antagonists have been found to attenuate memory formation in mice [2,3]. However, little is known about how dopamine affects aversive learning in humans. In this blog post, we review a recent publication from Nature that describes the role of dopamine in fear memory formation within the human amygdala.

Learning strength is linked to dopamine

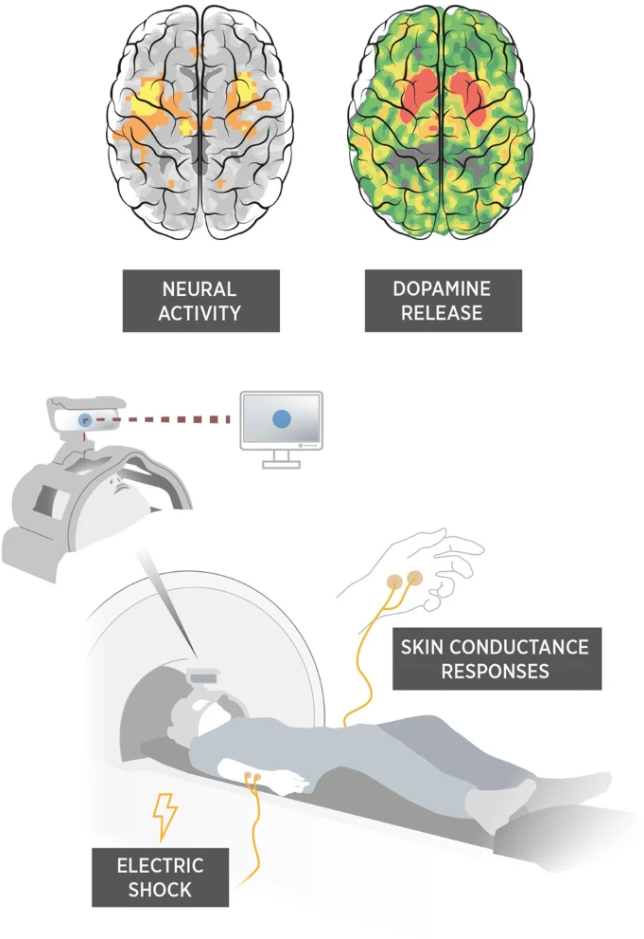

To investigate the links between dopamine release and aversive learning, Frick et al. simultaneously measured brain dopamine release and neural activity in a combined PET/MRI scanner before, during, and after fear conditioning (Figure 1). Two shapes were used as conditioned stimuli, one of which was paired with an electric shock 80% of the time, while the other was left unpaired.

Frick et al. demonstrated that human fear conditioning and learning strength is directly linked to endogenous dopamine release in the amygdala. These findings are consistent with previous rodent studies, indicating that this mechanism is evolutionarily conserved [2]. The authors also found that while learning strength was linked to dopamine release, the strength of the unconditioned response was not, providing further evidence of dopamine’s role in learning-related processes. Previous studies have also reported that fear conditioning can induce a greater increase in dopamine concentration than an independent shock.

One possible explanation for this mechanism is that dopamine serves as a neurochemical aid in strengthening aversive memory formation. This process is known as long-term potentiation, which refers to the long-lasting strengthening of synaptic connections following repeated signal transmission between two neurons [4]. Previous studies have shown that dopamine release in the amygdala facilitates fear learning, further validating the results obtained in this study [5].

Figure 1: Schematic illustration of the experimental design. Brain illustrations do not accurately reflect the results of the study. © 2022 Frick et al., licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Limitations and next steps

Although this study validated previous research on fear conditioning in the amygdala, there were a few limitations in this experimental design. Only 18 participants were recruited for this study, all of which are from the same town. A larger and more diverse cohort of participants could shine some light on whether these results were incidental.

While dopamine has traditionally been thought of as the pleasure chemical, this study highlights the multifunctionality of this neurotransmitter. Dopamine has also been implicated in locomotive learning [6], depression [7], and immunoregulation [8], and so we would be interested to see further research into its mechanisms.

About the Author

About the Author

Jasmin Skinner is an undergraduate student at the University of Western Ontario completing a Specialization in Biology and a Minor in Chemistry, with focused interest in applying these concepts to environmental conservation. As a lover of the outdoors and the arts, much of her time is spent in nature and within the local London art community, creating and connecting with all walks of life. After graduating, she hopes to continue her passion of finding unconventional solutions to environmental issues by working with nature, not against it.

References

- Frick A, Björkstrand J, Lubberink M, Eriksson A, Fredrikson M, Åhs F. Dopamine and fear memory formation in the human amygdala. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:1704–11. DOI : 10.1038/s41380-021-01400-x.

- Guarraci FA, Frohardt RJ, Kapp BS. Amygdaloid D1 dopamine receptor involvement in Pavlovian fear conditioning. Brain Res J. 1999;827:28-40. DOI: 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)01291-3.

- Guarraci FA, Frohardt RJ, Falls WA, Kapp BS. The effects of intra-amygdaloid infusions of a D₂ dopamine receptor antagonist on Pavlovian fear conditioning. Behav Neurosci. 2000;114(3):647–51. DOI: 10.1037/0735-7044.114.3.647.

- Cooke SF, Bliss TVP. Plasticity in the human central nervous system. Brain. 2006;129(7):1659-73. DOI: 10.1093/brain/awl082.

- Rogan MT, Stäubli UV, LeDoux JE. Fear conditioning induces associative long-term potentiation in the amygdala. Nature. 1997;390:604–7. DOI:10.1038/37601.

- Beninger RJ. The role of dopamine in locomotor activity and learning. Brain Res Rev. 1983;6(2):173-96. DOI: 10.1016/0165-0173(83)90038-3.

- Dunlop BW, Nemeroff CB. The role of dopamine in the pathophysiology of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(3):327–37. DOI: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.327.

- Sarkar C, Basu B, Chakroborty D, Dasgupta PS, Basu S. The immunoregulatory role of dopamine: an update. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24(4):525-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.10.015.

Additional fear-related neurobiology content

Bengoetxea de Tena et al. evaluate how naïve male Sprague-Dawley rats respond to a learning and memory task under fear conditions to evaluate the mechanisms behind fear extinction.

Raül Andero Galí presents findings from a recent study on sex-dependent differences in fear memory consolidation in mice.

Professor Paul Marvar and Benjamin Turley present research linking behavioral and cardiovascular responses with cued fear learning and demonstrate how post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can contribute to cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk.