Sugar, Spice, and a Troubling Vice: Cardiovascular and Cancer Risk with Artificial Sweeteners

Blog post by Jasmin Skinner

While sugar is a necessary part of a well-rounded diet, the amount of added sugar in most foods across the United States has raised concerns in recent years [1]. The average American consumes roughly 50% more than the recommended daily amount of sugar [1], which can result in insulin resistance, type II diabetes, fatty liver disease, and cardiovascular disease [2]. However, a simple solution for excessive sugar consumption already exists in many “diet-friendly” products. Artificial sweeteners like aspartame, sucralose, and saccharin provide more than a hundred-fold increase in sweetness per gram while also having a near-zero caloric effect, which can be highly desirable for individuals with diabetes or those looking to lose weight [3,4]. However, are artificial sweeteners a healthy and safe alternative to sugar?

Artificial sweeteners: sweet relief or grief?

While these artificial sweeteners sound like an ideal solution on paper, many researchers have highlighted some concerning side effects of these sugar substitutes, including bladder cancer, brain tumors, and weight gain [3,4]. However, the validity of these studies has been questioned, as few researchers have been able to replicate these results [3]. Despite these conflicting reports, artificial sweeteners have developed a reputation as a healthier alternative to traditional sugars, but two recently published studies by Debras et al. may shift the public’s perspective.

Study overview and outcome measures

In two similarly designed studies, Debras et al. sought to understand the links between artificial sweetener consumption and two common causes of mortality: cardiovascular disease and cancer. Participants were asked to provide some basic demographic and health information, and recorded their total dietary intake for 24 hours, 3 times per week. The authors evaluated intake for common artificial sweeteners such as aspartame, acesulfame potassium (Sunett® or Sweet One®), sucralose (Splenda®), and saccharin (Sweet’N Low® or Necta Sweet®), as well as other lesser known sweeteners. Cancer and cardiovascular disease risk were determined via declaration by the participants, as well as through comparisons with national health and insurance databases to limit potential bias from individuals not reporting an event.

Cancer risks associated with artificial sweeteners

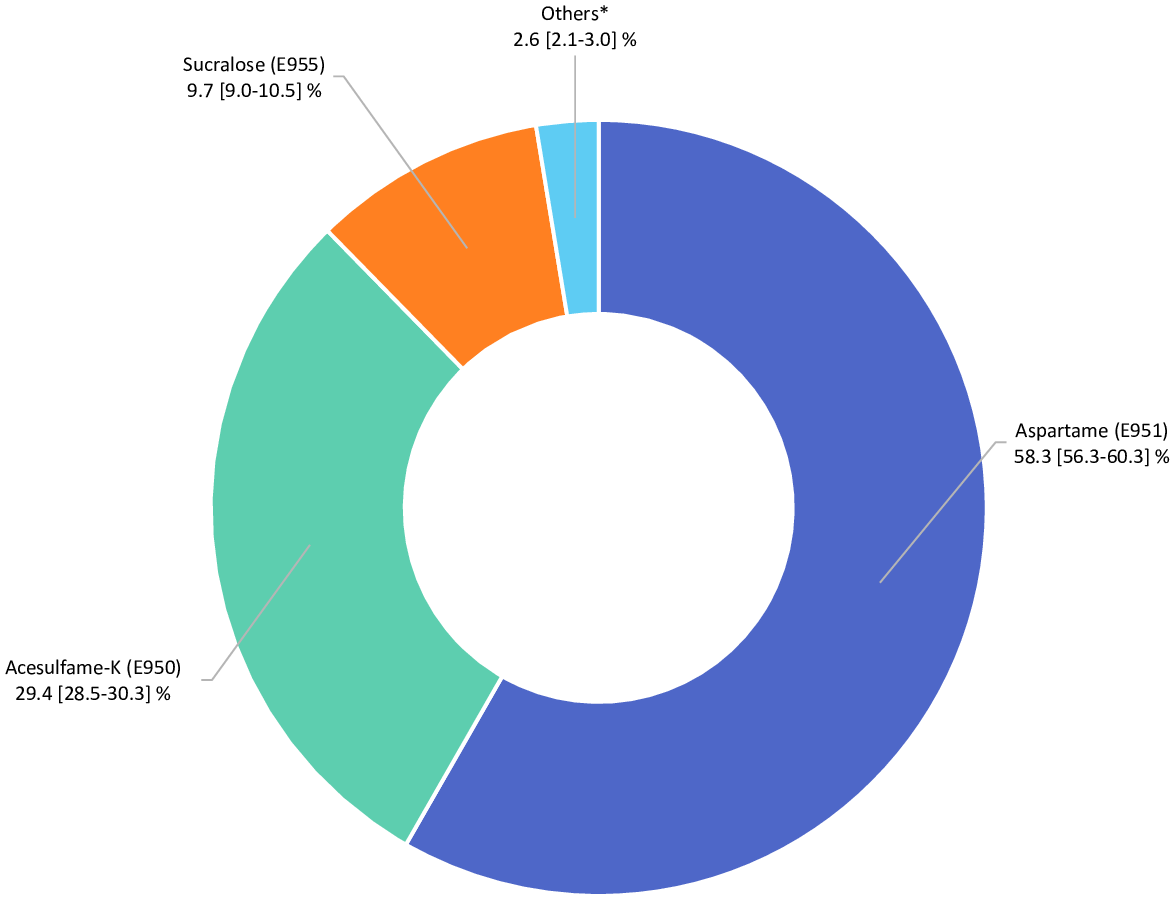

A positive correlation between high artificial sweetener consumption and overall cancer risk was observed [5]. Aspartame, which comprised approximately 58% of the total artificial sweetener intake in this study (Figure 1), was associated with an increased risk of breast and obesity-related cancers. Acesulfame potassium and sucralose, the second and third most consumed artificial sweeteners, respectively, were also linked to increased cancer risk. Sucralose has also been reported to cause malignant tumors in mice [6]. Previous studies have demonstrated that non-caloric artificial sweeteners are linked to gut microbiota modification [7], with dysbiosis and glucose intolerance being induced in mice and healthy humans. As similar changes in gut microbiota have been observed in cancer patients [8], the authors suggest that these changes might be involved in the development of some cancers.

Figure 1: Relative consumption of each type of artificial sweetener. © 2022 Debras et al., licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Artificial sweeteners and risk of cardiovascular disease

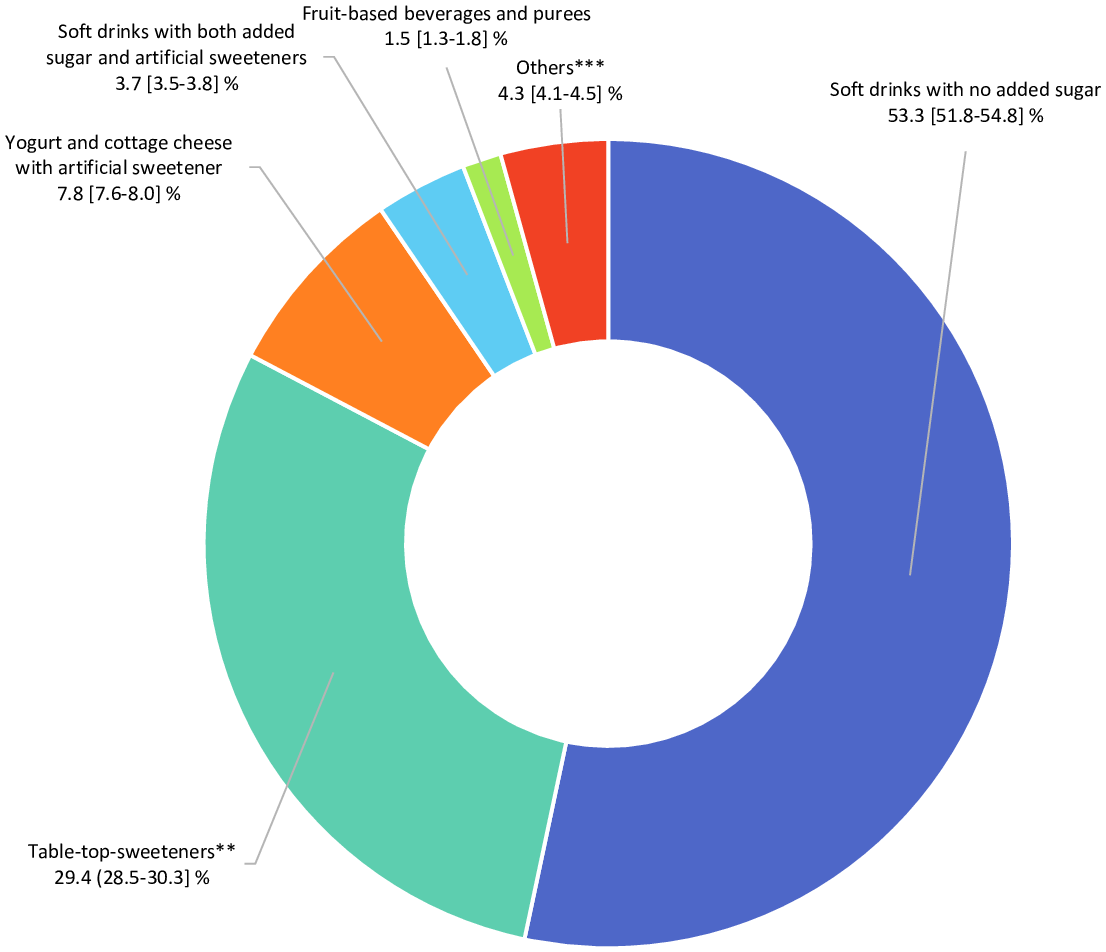

In their more recent study, the authors observed a potential direct association between higher artificial sweetener intake and increased risk of cardiovascular disease [4]. Aspartame was associated with an increased risk of cerebrovascular events, whereas acesulfame potassium and sucralose were linked to an increased risk of coronary heart disease. These sugar substitutes were most frequently consumed via soft drinks with no added sugar, as well as through tabletop sweeteners added to hot drinks or other foods (Figure 2). Based on these findings, the authors suggest that substituting traditional sugars with artificial sweeteners provides no benefit to cardiovascular health.

Are artificial sweeteners healthier than sugar?

Figure 2: Relative source of artificial sweetener in this study. © 2022 Debras et al., licensed under CC BY 4.0.

While associations between disease risk and artificial sweetener consumption were observed in this study, artificial sweeteners can be valuable for individuals with diabetes or for those trying to limit their caloric intake. The risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease appears to be less about what type of sweetener is consumed, but rather the quantity ingested. This observation also holds true for traditional sugars, as excessive sugar consumption is associated with an increased risk of hypertension, weight gain, diabetes, and fatty liver disease, all of which are precursors to cardiovascular diseases [2]. For instance, individuals who consumed high amounts of either sugar or artificial sweeteners exhibited no difference in cancer risk, suggesting that excessive consumption of either substance is the true culprit [5].

While the authors caution against considering artificial sweeteners as healthier and safer alternatives to sugar, further large-scale prospective studies are required to confirm the results obtained in this study. Furthermore, experimental studies should be conducted to determine whether sugar and artificial sweeteners have a differential effect on the cardiovascular system.

About the Author

About the Author

Jasmin Skinner is an undergraduate student at the University of Western Ontario completing a Specialization in Biology and a Minor in Chemistry, with focused interest in applying these concepts to environmental conservation. As a lover of the outdoors and the arts, much of her time is spent in nature and within the local London art community, creating and connecting with all walks of life. After graduating, she hopes to continue her passion of finding unconventional solutions to environmental issues by working with nature, not against it.

References

- Healthy Food America. Sugar advocacy toolkit overview [Internet]. Seattle: Healthy Food America. [unknown date] [cited 2022 Nov 03]. Available from: www.healthyfoodamerica.org/sugartoolkit_overview.

- Harvard Health Publishing. The sweet danger of sugar [Internet]. Cambridge: Harvard Medical School. 2022 Jan 06 [cited 2022 Nov 03]. Available from: www.health.harvard.edu/heart-health/the-sweet-danger-of-sugar.

- Gershenson G. A brief and bizarre history of artificial sweeteners [Internet]. Orlando: Saveur. 2017 Feb 23 [cited 2022 Nov 03]. Available from: www.saveur.com/artificial-sweeteners/.

- Debras C, Chazelas E, Sellem L, Porcher R, Druesne-Pecollo N, Esseddik Y, et al. Artificial sweeteners and risk of cardiovascular diseases: results from the prospective NutriNet-Santé cohort. BMJ. 2022;378:e071204. DOI: 10.1136/bmj-2022-071204.

- Debras C, Chazelas E, Srour B, Druesne-Pecollo N, Esseddik Y, Szabo de Edelenyi F, et al. Artificial sweeteners and cancer risk: results from the NutriNet-Santé population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2022;19(3):e1003950. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003950.

- Soffritti M, Padovani M, Tibaldi E, Falcioni L, Manservisi F, Lauriola M, et al. Sucralose administered in feed, beginning prenatally through lifespan, induces hematopoietic neoplasias in male swiss mice. J Occup Environ Health. 2016;22(1):7-17. DOI: 10.1080/10773525.2015.1106075.

- Suez J, Korem T, Zeevi D, Zilberman-Schapira G, Thaiss CA, Maza O, et al. Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Nature. 2014;514:181-6. DOI: 10.1038/nature13793.

- Huybrechts I, Zouiouich S, Loobuyck A, Vandenbulcke Z, Vogtmann E, Pisanu S, et al. The human microbiome in relation to cancer risk: a systematic review of epidemiologic studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29(10):1856-68. DOI: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-0288.