Celebrating Black Scientists: 5 Scientific Stories from the Past

Blog post by Jasmin Skinner

While often at the forefront of scientific discovery, the impact of Black and African-American scientists has historically been devalued, discredited, or intentionally suppressed (1, 2). As Black History Month comes to a close, this blog highlights some of these brilliant scientists and their enduring contributions to the life sciences.

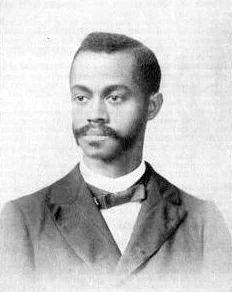

Charles Henry Turner, Advancing Understanding of Insect Cognition

Charles Henry Turner (1867-1923) was a behavioral scientist and was one of the first to study insect behavior. After completing his Undergraduate and Master’s degree in biology at the University of Cincinnati, Turner struggled to find employment at a major university in the United States, despite publishing more than 20 papers (3). For example, in 1892, he became the first Black scientist to be published in the prestigious journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, today known as Science (2). While not offered a university role, he held various teaching positions, and during this time also returned to college and completed a Ph.D. in Zoology at the University of Chicago in 1907. The following year Turner would settle down in St. Louis, Missouri as a high school science teacher, where he remained until his retirement in 1922 (3).

Despite not having access to traditional laboratories and research libraries throughout his career, Turner published more than 70 scientific papers. His breadth of research was expansive, and he often designed his own equipment to test various aspects of invertebrate awareness (3).

Figure 1: Charles Henry Turner, public domain.

A few examples include the development of a novel technique to study the visual abilities of honeybees, and the discovery that cockroaches can learn via Pavlovian conditioning. At the time, it was believed that social insects change their behavior in response to specific stimuli; Turner’s research demonstrated that insects can also change their behavior based on past experiences. In addition to his scientific accomplishments, Turner was also a prominent civil rights leader in St. Louis, and believed that only education could change racist behavior, drawing from his own research to explain the existence of different forms of racism (3).

Alice Augusta Ball, Innovative Student and Chemist

Figure 1: Alice Augusta Ball, public domain.

Alice Augusta Ball, (1892-1916) began her regrettably short career while obtaining a Bachelor’s Degree in Pharmaceutical Chemistry and Pharmacy, and published a 10-page article in the Journal of the American Chemical Society with the help of her pharmacy instructor (1). At the time, this achievement was remarkable not only as a woman but also as a Black person, considering the significant challenges faced by both marginalized communities during this period. For historical context, the Voting Rights Act, which gave Black and African-American women the right to vote freely, was not passed until 1965, 49 years after her death (4).

After graduation, Ball pursued her Master’s Degree in Chemistry at the University of Hawaii, where she studied chaulmoogra oil and its properties. While this oil was used at the time to treat leprosy, it lost efficacy when applied or injected (1). Ball found a solution to this problem by isolating the active compounds from the oil and modifying them to be water-soluble, allowing them to be easily absorbed by the human body while still remaining therapeutic (1).

This treatment would become the standard for leprosy patients until the 1940s but, unfortunately, Ball would not live to see this accomplishment, as she died in 1916 at the age of 24. Arthur Dean, a chemist and president of the University of Hawaii, published her research and manufactured the injectable chaulmoogra oil without giving any credit to Ball, although in 1922 an associate of Ball published a report attributing the discovery to her research. In 2020, a short film called The Ball Method was released to showcase this breakthrough discovery, more than a century after her death (1).

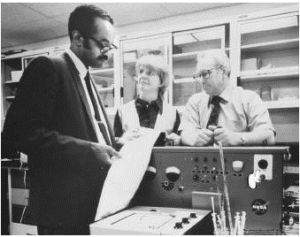

Emmett Chappelle, Breaking Biochemical Boundaries

Emmett Chappelle (1925-2019) was an American biochemist who made considerable contributions to the understanding and application of bioluminescence. His career had a delayed start, as after graduating high school he was drafted into the second World War. Once he returned to the United States, he completed several degrees, and also commenced his Ph.D. studies at Stanford University. However, he withdrew from the program when offered a position at the Research Institute for Advanced Studies, where he pursued research in methods to provide safe, breathable air for astronauts (5).

Figure 1: Emmett Chappelle, public domain.

Subsequently, he joined the Hazleton Laboratories in Virginia, which frequently collaborated with NASA on various contracts. During this time, he invented the ATP fluorescence assay, capable of detecting living cells using the two chemicals responsible for firefly bioluminescence: luciferin and luciferase (5). Although unsuccessful in its intended purpose to discover extraterrestrial life, its widespread applications in diverse fields such as agriculture, oncology, and genetics justify its consideration as one of the most significant biochemical inventions of the 20th century (5).

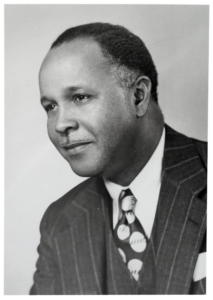

Percy Lavon Julian, Pioneering Medicinal Chemical Production Using Plants

Figure 1: Percy Lavon Julian, Courtesy of Science History Institute.

Percy L. Julian (1899-1975) was a distinguished chemist who developed several novel methods of producing medicinal compounds from plant matter. After receiving his Ph.D. from the University of Vienna in 1931, he joined the DePauw chemistry program as a research fellow in 1932, during which time he produced a number of important publications. One such paper, titled “Studies in the Indole Series V. The Complete Synthesis of Physostigmine (Eserine),” describes the synthesis of physostigmine, a compound used to treat glaucoma (6). This was particularly notable as this compound had not previously been created in the laboratory, greatly improving the availability of treatments for this disease. Despite his achievements, the Board of Trustees at DePauw University would not allow him to join the teaching staff, likely as a result of racial biases. This setback would not deter his motivation for scientific innovation as around 1950, he founded his own laboratory, “Julian Laboratories” (6).

After this extraordinary accomplishment Julian and his family moved to an affluent Chicago suburb, and were the first Black family to do so. Although opposition was not universal, some residents objected to their presence, resulting in two separate bomb attacks at the Julian residence. Undeterred, Julian confidently moved forward in his career, and was ultimately appointed to the DePauw University Board of Trustees in 1967, the very same board that had rejected him 30 years prior.

His legacy at the university lives on, with his spirit of student faculty collaboration continuing to the present day. Julian’s scientific innovation led him to a distinguished career in the chemical industry, as his numerous patents for medicinal compound manufacturing still hold merit to this day. For example, his method of synthesizing glucocorticoid 11-deoxycortisol (then called Reichstein’s Substance S) was the most widely used method for the production of hydrocortisone and its derivatives for more than 50 years (6).

Alexa Canady, Paving the Way for Pediatric Neurosurgeons

Dr. Alexa Irene Canady (B: 1950), was the first Black woman to be certified as a neurosurgeon by the American Board of Neurological Surgery in 1984. By her own account, her career began trepidatiously as, while in college pursuing a mathematics degree, she “had a crisis of confidence” and considered withdrawal. However, after learning of a minority scholarship in medicine, she felt “an instant connection” and earned a spot at the University of Michigan Medical School, where she graduated cum laude in 1975 (7).

Despite her impressive credentials, Dr. Canady still faced prejudice throughout her career. On her first day of residency, a senior administrator remarked while passing through her ward, “Oh, you must be our equal-opportunity package.” However she remained undeterred, and was the Chief of Neurosurgery at the Children’s Hospital of Michigan from 1987 until her retirement in 2001.

Figure 1: Alexa Irene Canady, public domain.

In her 20 years as a pediatric neurosurgeon, Dr. Canady treated patients with head trauma, life-threatening diseases, gunshot wounds, and a myriad of other brain injuries or diseases. She has received two honorary doctorates, one from the University of Detroit-Mercy awarded in 1997, and another from the University of Southern Connecticut, awarded in 1999. In addition to these degrees, she has also received several awards for her contributions to neurosurgery, and has been inducted into the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame (7).

While still facing significant obstacles, the contributions of Black and African-American scientists are invaluable to the advancement of their respective fields. It is important that we recognize and celebrate the accomplishments of these individuals, not only during Black History Month but throughout the year, as we continue to work towards a more diverse and inclusive scientific community.

About the Author

About the Author

Jasmin Skinner is an undergraduate student at the University of Western Ontario completing a Specialization in Biology and a Minor in Chemistry, with focused interest in applying these concepts to environmental conservation. As a lover of the outdoors and the arts, much of her time is spent in nature and within the local London art community, creating and connecting with all walks of life. After graduating, she hopes to continue her passion of finding unconventional solutions to environmental issues by working with nature, not against it.

References

- Live Science Staff. Amazing Black scientists [Internet]. New York, NY, (US): LIVESCIENCE; 2023 Feb [Cited 2023 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.livescience.com/amazing-black-scientists.html

- Buckiewicz A & Weikle B. Meet 7 groundbreaking Black scientists from the past [Internet]. [Place unknown]: CBC Radio; 2021 Aug [cited 2023 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/radio/quirks/black-scientists-history-1.5918964

- Abramson CI. Charles Henry Turner [Internet]. [Place unknown]: Britannica; 2023 Feb [cited 2023 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Charles-Henry-Turner

- Bailey M. Between two worlds: black women and the fight for voting rights [Internet]. Washington, DC, (US): National Park Service; 2022 Sept [cited 2023 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.nps.gov/articles/black-women-and-the-fight-for-voting-rights.htm

- Hidayat A & Chmiel R. Black history month series 2020: Emette Chappelle [Internet]. [Place unknown]: Broader Impacts Group; 2020 February [cited 2023 Feb 23]. Available from: https://web.whoi.edu/big/black-history-month-series-2020-emmett-chapelle/

- Percy L. Julian and the synthesis of physostigmine [Internet]. [Place unknown]: American Chemical Society National Historic Chemical Landmarks; 1999 April [cited 2023 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.acs.org/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/julian.html

- Dr. Alexa Irene Canady [Internet]. [Place unknown]: Changing the face of Medicine; 2003 October [updated 2015 June; cited 2023 Feb 23]. Available from: https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_53.html