The Blues & the Browns: Links between Depression and Gut Microbiota

Blog post by Jasmin Skinner

Despite depression being a leading cause of disability and affecting roughly 5% of adults worldwide, available treatment options remain limited (1). While antidepressants can be helpful in the short-term, they perform only marginally better than a placebo (2). Furthermore, existing treatments for persistent depression are often invasive and may require surgical procedure, such as with vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) (3). Since the onset of the pandemic the incidence of depression has doubled or tripled in some countries, with the global lifetime prevalence increasing from 11-15% to 33.7% (4). It is clear that while current methods of treating depression address many of the symptoms, few actually address the root cause.

In recognition of this, attempts to fully characterize the underlying pathogenesis of depression are well documented, but to date none have been entirely successful. This is perhaps unsurprising given the complexity of the illness itself, as both genetic and external factors influence whether an individual experiences depression. For example, according to a large Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) of depression, heritability was low to moderate, indicative of the importance of other factors including pathways beyond the central nervous system (2).

In this blog post, we discuss a recent breakthrough for gastrointestinal disorder diagnosis: ingestible biosensors capable of providing real-time measurement of a wide range of biomarkers and therapeutic targets. READ HERE

Why have gut microbiota been associated with depression?

Several animal studies have suggested that the gut microbiome impacts some of the neurobiological features of depression. For example, transfer of gut microbiota from human participants with depression to non-depressed rats evoked behavioral and physiological changes consistent with depression in recipients (2). This effect appears to be consistent with other neurological disorders such as anxiety, and also metabolic conditions like obesity.

While this is certainly enough evidence to argue that the gut microbiota may influence the nervous system in rodents, few studies have systematically analyzed this association in humans. Most studies to date included very small sample sizes, making it difficult to assess the reproducibility or validity of the findings. To address this information gap, a recently published study compared depression scores with gut microbiome diversity and composition in over 2500 individuals, while controlling for lifestyle factors and medication use (2). Mendelian randomization was then performed to determine whether a causal relationship exists between depression and certain gut microbiota.

What is the link between the gut microbiome and depression?

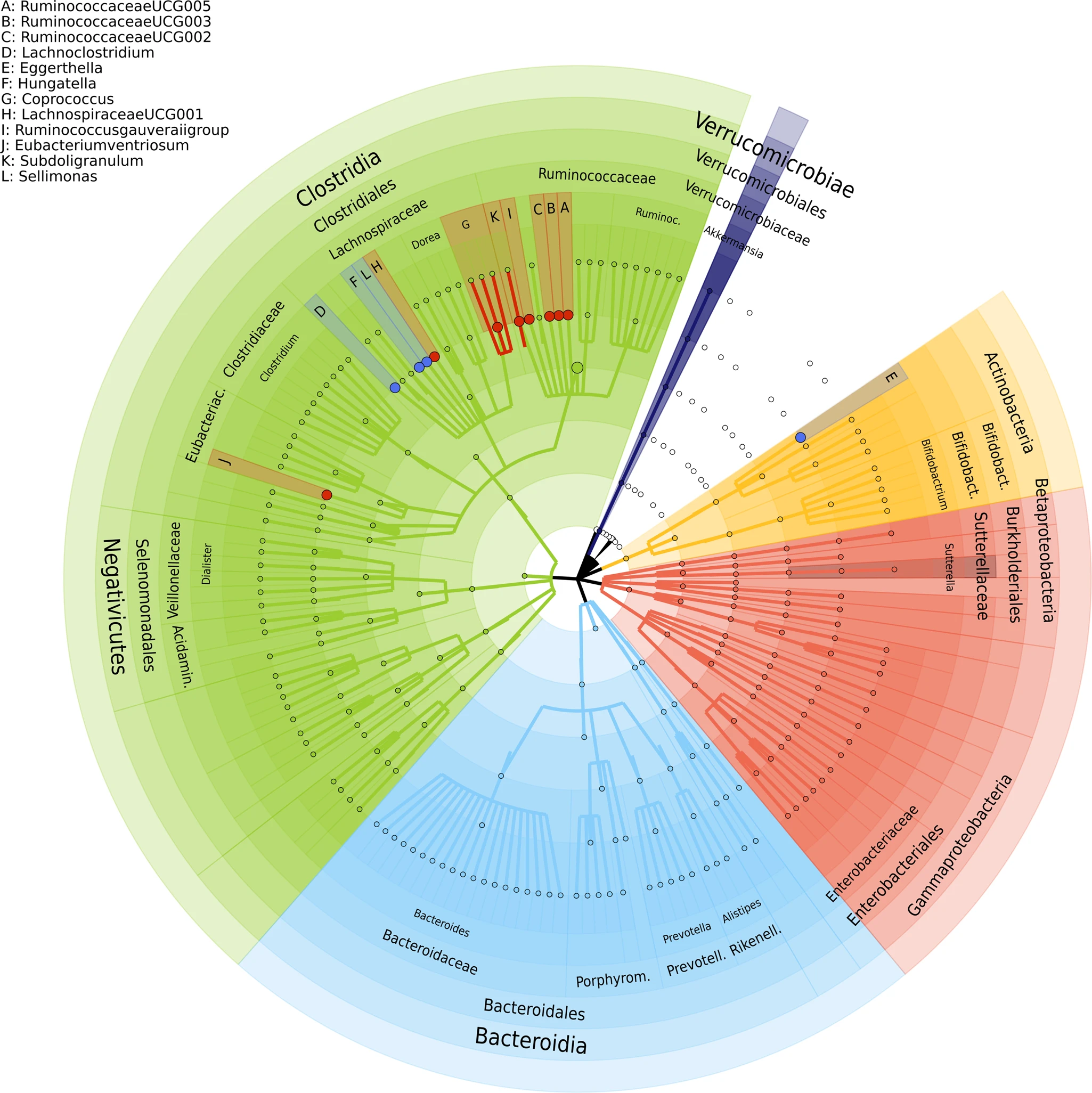

Following statistical analysis, 12 different genera and one microbial family, Ruminococcaceae, were found to be associated with depressive symptoms. Four taxa in particular, Sellimonas, Eggerthella, Lachnoclostridium, and Hungatella, were found to be elevated in individuals with more severe symptoms of depression, whereas the remaining eight taxa were depleted in depressed patients. Additionally, a more diverse gut microbiome was also significantly associated with depressed symptoms, suggesting a multitude of factors are likely involved.

Previous studies have also shown that the intestinal bacterial strains Eggerthella, Subdoligranulum, and Coprococcus have been linked to depression, aligning with the findings of this paper. A recent fecal transplantation study found that Coproccocus was depleted in rats that exhibited depressed behavior upon fecal transplant from depressed human patients, suggesting a causal effect. Additionally, eight separate studies have found Eggerthella to be consistently elevated in patients with depression and anxiety, and MR analysis also suggests a causal link between Eggerthella and depression. However, further investigation is required to better understand the gut-brain connection.

Figure 1: The identified 13 genera associated with depressive symptoms. © 2022 Radjabzadeh et al., licensed under CC BY 4.0.

How do gut microbes affect depression?

Many of the microorganisms discussed in this study are implicated in glutamate and butyrate synthesis. Glutamate, a major excitatory synaptic neurotransmitter, has been previously associated with mood and psychotic disorders when elevated or depleted in the plasma, serum, cerebrospinal fluid, or brain tissue. Recently, glutamate receptors have become an increasingly popular therapeutic target for depression, with treatments like ketamine seeing greater support as an alternative to more traditional antidepressants.

On the other side of the gut-brain axis, butyrate, a short chain fatty acid, reduces inflammation and oxidative status in the gut (5) through enhancement of cholinergic neurons, and can even cross the blood-brain barrier and activate the vagus nerve and hypothalamus. This nerve and brain region are particularly relevant, as vagus nerve stimulation has been used to treat seemingly “untreatable” depression (3), and those with depression have been observed to have a larger hypothalamus on average (6). Subdoligranulum and Coprococcus, two genera associated with depression in this study, are also involved in the production of butyrate. Previous studies have reported that individuals with depression and anxiety had less of these microbes, providing further evidence in support of a role for butyrate.

What do the results of this study mean for the future of depression treatment?

Although the findings may help identify a new and somewhat unconventional target for the treatment of this and other mental health disorders, additional research, development, and validation is required before effective translation to the clinic. Consequently, although methods of modifying the gut microbiome already exist, such as the use of fecal transplantation to treat bacterial infection, their application in the treatment of mental illness remains in its infancy (7). Nevertheless, as the global prevalence of depression continues to increase, the introduction of novel approaches is welcomed and may provide hope in the near future for those who continue to suffer.

About the Author

About the Author

Jasmin Skinner is an undergraduate student at the University of Western Ontario completing a Specialization in Biology and a Minor in Chemistry, with focused interest in applying these concepts to environmental conservation. As a lover of the outdoors and the arts, much of her time is spent in nature and within the local London art community, creating and connecting with all walks of life. After graduating, she hopes to continue her passion of finding unconventional solutions to environmental issues by working with nature, not against it.

References

- Depression [Internet]. [place unknown: World Health Organization]; 2021 Sep 13 [cited 2023 Jan 26]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression

- Radjabzadeh D, Bosch JA, Uitterlinden AG, Zwinderman AH, Arfan Ikram M, van Meurs JBJ, et al. Gut microbiome-wide association study of depressive symptoms. Nat. Commun. 2022;13(7128). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34502-3

- Tisi G, Franzini A, Messina G, Savino M, Gambini O. Vagus nerve stimulation therapy in treatment-resistant depression: a series report. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014; 68(8):606-11. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12166

- Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, Vaisi-Raygani A, Rasoulpoor S, Mohammadi M, et al. Global Health. 2020;16(57). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w

- Canani R. Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(12):1519. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3748%2Fwjg.v17.i12.1519

- Schindler S, Schmidt L, Stroske M, Storch M, Anwander A, Trampel R, et al. Hypothalamus enlargement in mood disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;139(1):56–67. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/acps.12958

- Doll JPK, Vázquez-Castellanos JF, Schaub AC, Schweinfurth N, Kettelhack C, Schneider E, et al. Fecal microbiome transplantation (FMT) as an adjunctive therapy for depression – case report. Front. Psychiatry. 2022;13(815422). Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.815422